— Objects

Hereafter tracks the last years of the British empire through an investigation of the life of the photographer’s grandparents and their progeny. Carefully sewing together the history of his family and the history of British colonialism, the shaping of Hereafter began in 2013 in response to the photographer’s need to reconnect with his British grandparents; his grandmother, Mary Phillips, and his grandfather, John Phillips, who passed away in 1998 when the photographer was very young. Visiting his grandparents house in Horsham in 2013, he notes:

“I remember this feeling of going through drawers, albums and things and feeling that I had the opportunity to address my grandparents life through them. It was the objects that spoke first. I remember all these things sitting in the dark or in the bottom of drawers, and being like unanswered questions. So you could be fascinated by the way they were strange and in the same time be curious about what they meant, where they came from and what was the web that brought together these objects in that place. And the key to that was what my grandmother was capable of remembering.”

The unspoken histories of familial objects led Clavarino to initiate dialogues with his grandmother, which in turn unlocked the histories of the family. During that first visit Clavarino began to quickly photograph the objects with his father’s digital camera. In his second visit, he returned to the house with a medium format Mamiya - but it still didn’t feel quite right. Ultimately, Clavarino decided to invest on a large format technical camera, which gave him the possibility to approach the house, the objects and the portraits in a slower manner; “a process in which you stage and stare at the objects”. Clavarino remarks;

from HEREAFTER @Federico Clavarino

“At the beginning of the project I didn’t really know where it would take me. I had identified the fact that there were these two things; the first had to do with my family, my grandmother, the fear that she would die, and with this encounter with my grandfather [through the objects and ephemera found in the house]. The second was this whole thing about empire and this idea of something in history that has been disavowed and the way it could live within a family archive”.

This binary structure - doubtlessly difficult to concile - identified during the initial stage began to define the shape of the project, moving beyond an initial, visceral reaction to the space and the objects.

“I learnt to know the house and the light that would change according to the time of day and the year… It was fascinating because different corners of the house became visible; suddenly it was summer and the light would come in through a different window at a different time of day and the corners that were previously unlit became lit, and could become the backdrop of photographs.”

from HEREAFTER @Federico Clavarino

Rather than displacing the objects and photographing them in a cold, documentary manner placed against a white anonymous background, Clavarino photographed them “as they were and slowly became visible”, taking pictures of them as they were progressively discovered. Whilst many objects were photographed, plenty of other materials such as newspaper clippings, archival photographs and documents were instead scanned, and have a different function within the photobook.

— Conversations

Hereafter is significantly imbued with the conversations which occurred between Clavarino and his family members - not only his grandmother, but also her children. The conversations took on different shapes and formats depending on who was the interlocutor.

“Most of the conversations with my grandmother were very natural and I would just sometimes turn on the recorder when I felt something important was being said. She was very happy to have the opportunity to tell stories and eager to share them and remember things of happier moments of her life, because I think she felt nobody really cared. Obviously after a while it became a bit repetitive. She would focus on a set amount of anecdotes, and you would notice how these anecdotes were selected and remembered, and that had to do with what was probably more ‘comfortable’ to remember. I think those anecdotes also supported, or had supported, her world view. It was interesting to see what she forgot and what she remembered - and you also had a very partial access to what she forgot or decided not to tell from what other people would tell or what you found in documents. [...] This is something very important about the project: all the empty spaces and the way in which narrative and history are not only based on remembering but are also built on what is forgotten.”

from HEREAFTER @Federico Clavarino

In regards to the other members of his family, the more the project proceeded the more the conversations became structured. With an increased understanding of what he was looking for, Clavarino would arrange meetings and go to their houses with a prepared set of questions.

—Travels

After receiving a grant from Fotopres La Caixa, Clavarino suddenly found himself able to travel to the sites where his grandparents lived during the years in which John worked as British ambassador. Because the funds were not enough to travel to all the countries the family lived in, he decided to focus on the countries in which they spent the longest time: Oman, Jordan and Sudan.

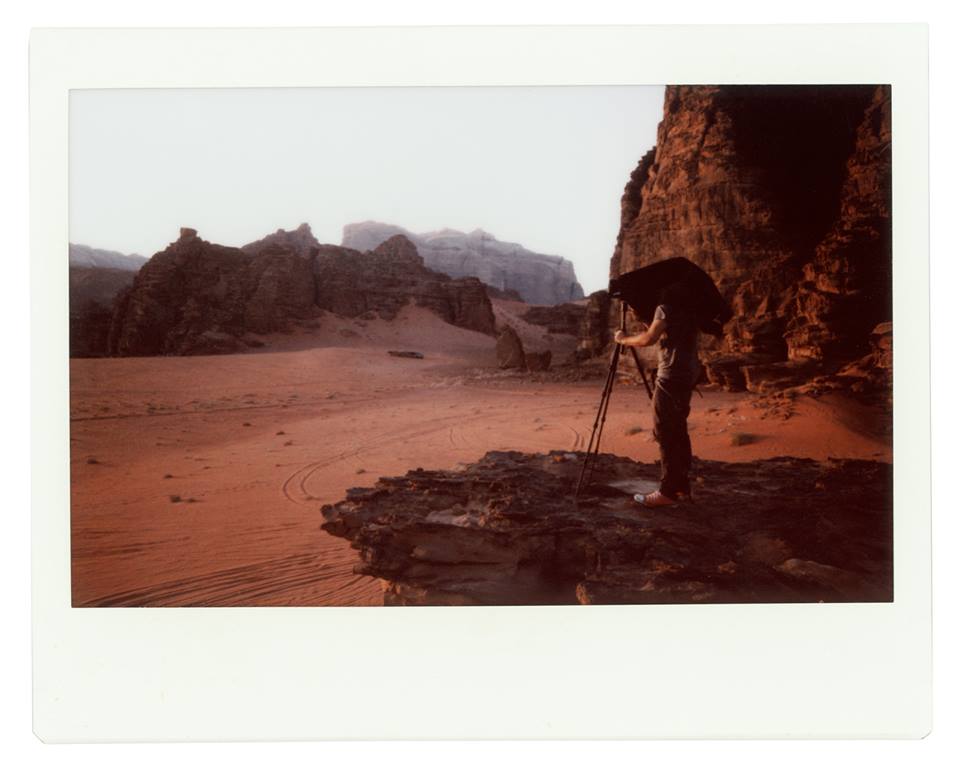

Federico at work for HEREAFTER

from HEREAFTER @Federico Clavarino

“The opportunity to travel meant I could see something more for myself. I felt that was exactly what could help me make the material I had more complex and not fall into a kind of very straightforward portrayal of colonial nostalgia. That was something I always very consciously wanted to avoid. So I thought that by bringing in this other material and making it work together with what I already had - which was basically other people’s voices - I could bring in the way in which I was there and how that was partly determined by the way my family had been there before me, by what I had been told and what I saw. I didn’t have the ambition to ‘say everything’, as it would have been impossible. It was more about laying out a series of tensions and contradictions. So that was the thin and very delicate line I was trying to travel on, but it was tricky, as in the end the way I was working was a semi-controlled drift. I had a series of points and places which had to do with stories, but everything in the middle of empty and open to chance. This made everything more permeable and vulnerable, because I wasn’t working on a preselection of choices. It allowed me to be there, exposed, and absorb everything like a sponge.”

— Editing

After coming back from the various journeys Clavarino found himself with hundreds and hundreds of images to work through and make sense of: the photographs taken in his grandparents house, the scanned archival material and ephemera, the transcripts of conversations and the images of the travels.

“All of that went through an initial selection and printed small, including a selection of parts of the transcripts which I screenshot and printed out. Because the material was so much I had to rent a studio for a few months. I needed a very big space to map it out, or at least map out part of it, because the togetherness of all the material didn’t fit also when I entered the studio. It took me three months to take it down to something I could take away and work with at home. But the whole process was probably a year long - you also need a lot of time in between to digest what is there and understand how to structure the material.”

The decision to divide the book into five chapters, and that every chapter would correspond to a specific place, was taken in order to facilitate the massive editing operation Clavarino was faced with. The first chapter brings together the material from the domestic space of his grandparents and introduces the story through his ancestors, “the phantom of empire and the way it lurked in all the dark corners of the house”. The second, third and fourth chapters focus respectively on Oman, Jordan and Sudan, each exploring a different aspect of the same problem; the British empire. In the case of Oman, the photographs taken during his travels were associated to the story told by his uncle William on the birth of the country, the exploitation of resources and the sale of infrastructures which lead to the coup and the removal of the old Sultan. The chapter on Jordan, which was also born through geopolitical engineering on behalf of Britain and France, focuses on the formal relationships between diplomats, “made of an iconology of hand-shakes, letters passed on, smiles, and this idea of communication, or interference with communications, and empty words and formalities”. The penultimate chapter highlights the way his grandparents perceived their role and their presence in Sudan, and the ways in which their views and interpretations of their surrounding were part of the process which shaped stereotyped ideas about native tribemen. The last chapter, The Quantum Soul, brings the project to an end through a reflection on death, the afterlife, and the cyclicity of history in which Clavarino also re-inserts himself into the picture. Reflecting on his editing process, he comments:

HEREAFTER exhibited at Caixa Forum

“What I didn’t want to do is to have some kind of preconceived idea of what things mean, or should mean, and find examples - that would have been boring and dishonest. I find more interesting to build the thought whilst I work, to allow the images I find to echo the words I have heard… and that enters a system that is being built whilst I work. It’s lived experience. And then you have moments in which all that lived experience is meditated upon and structured and made understandable, but the idea is that you don’t want to just take all of that and explain what it means to you… you need to get it over to someone else with the same degree of complexity and in the same time provide some kind of key for people to work with. You want the reader to work, because that’s when the reader can provide extra content and interpret, re-live it and add to it. And that becomes a way to share the work instead of imposing it.”

— Book Production

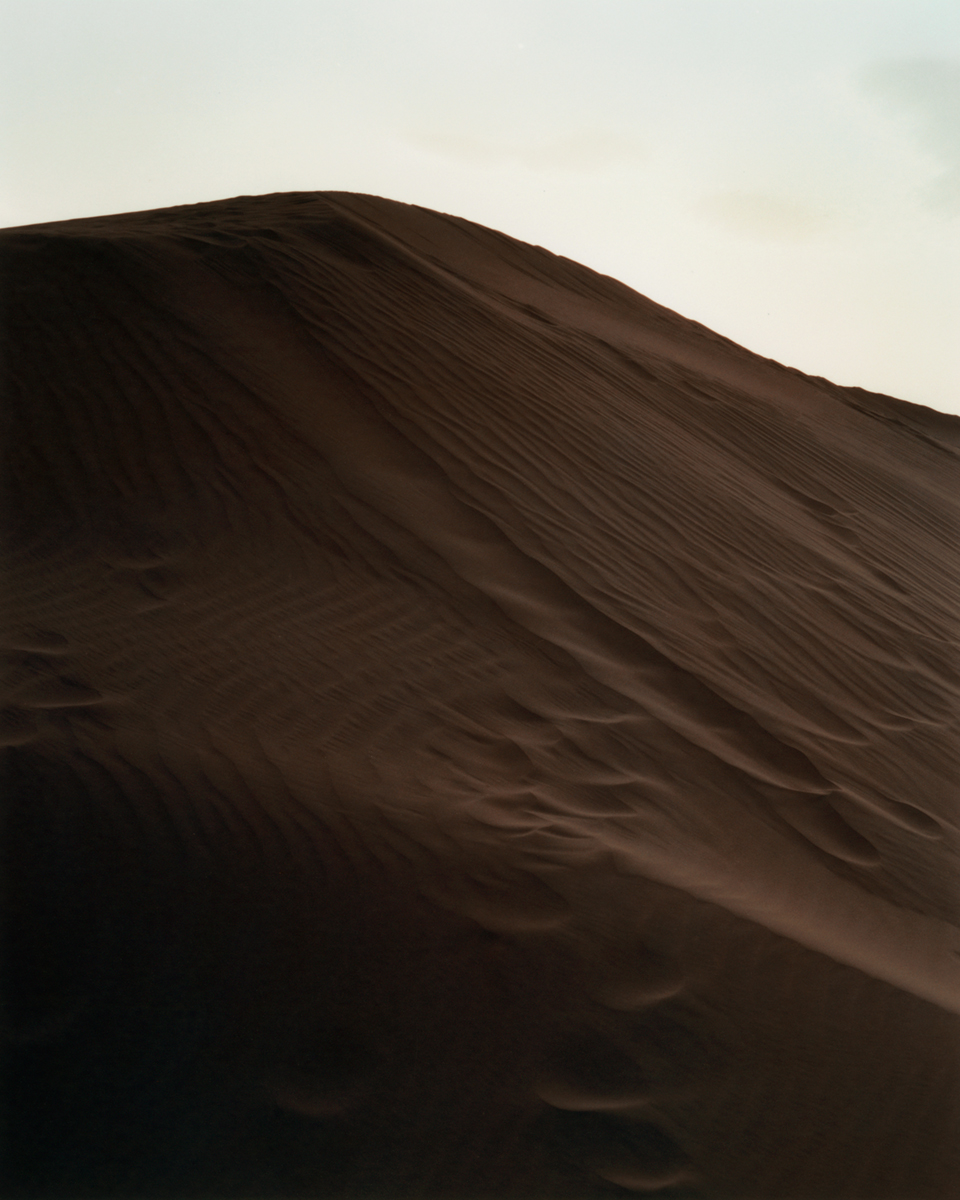

Clavarino’s describes himself as “obsessed with color and the materiality of the print”, and his production of color photographs entails a painstaken, laborious process. For the production of Hereafter, he printed a selection of photographs in the color darkroom at Lab35 in Madrid with the support of his long-term colleague Jose Luis Perez, producing over 180 C-type analogue prints. To have full control over color balance and subtle hues and tones, the prints were then scanned on a flatbed scanner alongside the archival material. The final color-balance of the images is thus the result of a mixture of digital and analogue processes of color correction, undertaken in order to make the material coherent.

Last Dummy of HEREAFTER

“If you notice, every chapter has a particular color palette. I believe in these things in the sense that it’s like… the voice, or the music of the work - it has a power, it has a tone. So every chapter has its own, and I worked on that very consciously both when I was editing and then printing the work and then re-working the color digitally. Then all that was made into a dummy book.”

For the draft of the book Clavarino worked with Tres Tipos Gràficos, a group of Madrid-based graphic designers, which he had already worked with for the making of Italia o Italia and The Castle.

“What usually happens is that I make the sequence, a rough design, and then they fix it. But for Hereafter it was a lot more complex. I didn’t know how to use InDesign (now I have learnt a little bit), so I created every single page on Photoshop, and gave it to them saying: this is how the book works. Esther Madrazo, my assistant at that time, who is a brilliant designer, did a lot of the actual balancing of every page. We had grids created by the designers and she would place the images and the text within the grids so that everything was balanced and felt good. The cover was tricky too. That was probably the thing on which the designers worked on the most. They came up with it… at the beginning I was very surprised, seeing my name that big, I didn’t like it. Usually it’s never there on the covers of my books, so I was rather reluctant. But they convinced me of the way it worked and I like it very much now! It’s like an architecture of the cover, more than only text.”

Federico checking colors during the production of the book

For the first draft of the book, Clavarino produced five maquettes which were moved around and the book was one of the finalists of the LUMA Dummy Book Award at Arles Photo Festival, which allowed him to receive some early feedback. In the first dummy, almost 400 pages long, the found material, his photographs and the text were laid out in small constellations on every spread, shared the same space, and there were notes at the end of each chapter. The rhythm created by the repetitiveness of the layout strategy, as well as the exorbitant amount of materials and notes, made the reading of the book a little too chaotic and demanding.

“It was a bit too much… it felt like these very white blocks with all these little floating islands. So in the end we decided to give a stronger structure to each page, and I had the idea of dividing the found material and use it to separate each chapter and abolish the notes. So I integrated part of the notes within the chapter, and used the found material as notes, printing them on a different paper, which means you have this first reading of my photography and the text that is played together, and the rest is a bit more analytical, so you have all of this research material at the end of each chapter to make things more complex and have more information. So ideally, if you want you can go through the book a first time without even looking at the found material and already have a sense of what is going on and how it works, and then go deeper into it by also integrating the found material and getting more from the letters, the text, the people in the images, matching them with the voices, and so on. On one hand it made it a bit more easier for the reader, and on the other it meant that actually if you wanted you could get even more out of it.”

With the second edit of the book they managed to bring the page number down to 300 or less, allowing for the price of acquisition and shipping to drop, making the book accessible for a wider audience.

“Nonetheless, the book had to be large, because you had to be able to read the text in the images and in the letters and so on… so you needed room to make that work. And in the first dummy, all the found material was reproduced in scale! I had to give up that rule in the second version because in the end it was a bit arbitrary and tyrannical. So what I did was to try and maintain the proportions but shrink everything a little bit to make it fit.”

Once the second draft was ready, the printing process with Skinnerboox began.

First sheet of HEREAFTER

“I am a bit obsessive, so I need digital color proofing, then I need offset color proofing, then I need to go to the printer and supervise every single page because I want everything to be good. I think for many photographers the process of printing a book can be a little disappointing, as you are used to high quality printing, especially when printing in the darkroom. And then when you go to offset it’s always so different, so it can be frustrating. But it went well, the printer was good, and over the years I learnt how to respect and understand the work of the technicians and learn what they can and what they can’t do. Skinnerboox has been profoundly supportive and enthusiastic throughout the project, and took a great risk with my book: it’s big, it’s expensive to make, it’s a gamble, it’s a book with a lot of text in a market in which people are not very keen on reading text, and it’s a tricky subject. So as a publisher that is probably risky, but Milo has always gone with it, and allowed me to make the book I wanted to make. It’s been a very good collaboration.”

Federico Clavarino in conversation with Benedetta Casagrande

March 2019