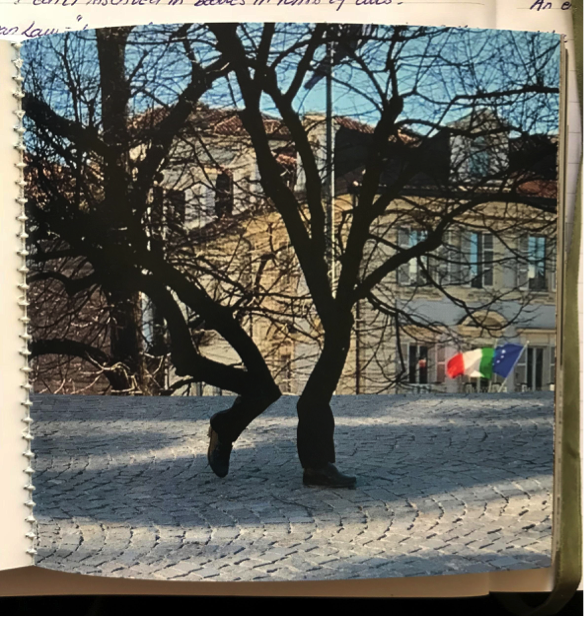

Footsteps echo in the piazza. When we turn to greet the lonely wanderer we are received by two elegantly dressed feet. They do not belong to one character; rather than walking in unison, they are hopping - two singular, elegantly dressed feet taking their trunk for a walk. Behind their waving branches, the familiar landscape of the Italian province - probably a municipal building - embellished with the Italian and the European flag. I would like to ask them where they are going, but it is renown that trees do not have ears to listen or mouths to reply with.

Simone Sbarbati described Fontanesi’s instagram account as the sketchbook of a character designer, “and where there is a character, it is safe to assume that what we have in our hands is an ingredient for a potential story”[1]. And if picking one single image out of his “encyclopedia of creatures” has been an ordeal, to describe it without employing a novelistic approach would have been impossible, for Fontanesi’s creatures insistently probe our imagination and beg us to weave them a story, animate their movements, fantasies about their past and future, listen to the sound of their footsteps.

Cut and restored, Fontanesi’s creatures are fruit of a simple yet effective mounting technique which splits the image in half and recomposes it by enlarging, reflecting, shifting and matching bodies: natural and artificial, these new transformers blur the separation between subject-object, turning objects into “things that feels”, subjects into practical tools, men and women into genetically modified (or better, digitally mounted) monsters. Which bodies - both real and abstract - are being cut to produce this atlas of “modern provincial folklore”? And what is created by these recombinations?

Let’s start by considering the setting for Fontanesi’s characters: the Italian province. In the essay Cut! Reproduction and Recombination, Hito Steyerl reflects upon the term ‘cut’ as used both in cinematography and in economics, the former referring to the mounting of sequences, the latter to the reduction of “government spending on welfare, culture, pensions and other social services”[2]. Gripped by a public debt which has been steadily increasing for over ten years, the Italian government has issued severe cuts in a variety of social services (first and foremost education and pensions), and currently faces an unemployment rate of 10,2% - the third highest unemployment rate in Europe after Spain and Greece. In the midst of debt, economic depression and migration crisis, Italy is subject to “a hyperinflation of metaphors of pure national-social and racial bodies”[3], the pervasive slogan of the current Minister of Interiors being “Italians First”. And as cuts are being enforced on the metaphoric economic body of the State, non-white, racialized bodies are wounded on the street: a twelve years old Egyptian boy hospitalized after being beaten up for the third time in February 2019, a Gypsy mother with her daughter verbally assaulted by a representative of Casa Pound, black men ran over and beaten under the accusation of being black.

The socio-political landscape I described feels far from the humorous, magically twisted province created by Fontanesi. Yet, these pixelated creatures which mash-up genders, objects and limbs allow us to imagine a social body that deviates from existing configurations of class, race and gender. Reflecting upon Siegfried Kracauer’s ideas on the potential of recombinations of bodies expressed in The Mass Ornament, which took the Tiller Girls as a starting point to argue for a radicalization of fragmentation, Steyerl suggests:

“The industrial body of the Tiller Girls is abstract, artificial, alienated. Precisely because of this, it breaks with the traditional and, at that time, racially imbued ideologies of origin, belongin, as well as with the idea of a natural, collective body created by genetics, race, or common culture. [...] Kracauer saw the anticipation of another body, which would be freed from the burden of race, genealogy and origin - and we can add, free of memory, guilt and debt - precisely by being artificial and composite”[4]

Described by Stefano Riba as “post-truth, post-identity, post-human”, the hopping trees which traverse the province are genderless and raceless. In Fontanesi’s world, all bodies are legitimate; mono-legged horses, macrocephalous men, two-headed women. The story I wish to tell through Fontanesi’s characters is one of striking inequalities, but also one of possibilities; an imaginative exercise through which we can reconsider our ideas on subjecthood and identity. Perhaps, we should stop expecting photography to deliver us a ‘truthful’ representation of an essential identity bound to race, class and gender (if that even exists), and start questioning by what means could it provide a pool for our creative minds to dive into and reimagine a radically reformed social body.

The legged trees hopped away into the lazy Sunday of the Italian province, nobody questioned where they came from or whether they had the right to be there, and they went about their day enjoying the sunshine.

The first book by fontanesi, “GRANDISSIMA SELEZIONE” is available here

Benedetta Casagrande

Photographer, writer, curator

[1] Sbarbati, Simone, Grandissima Selezione: arriva il primo libro di fontanesi, frizzifrizzi.it

[2] Steyerl, Hito, Cut! Reproduction and Recombination, The Wretched of the Screen, eFlux, pp. 177

[3] Ibid.

[4] Steyerl, Hito, Cut! Reproduction and Recombination, The Wretched of the Screen, eFlux, pp.181