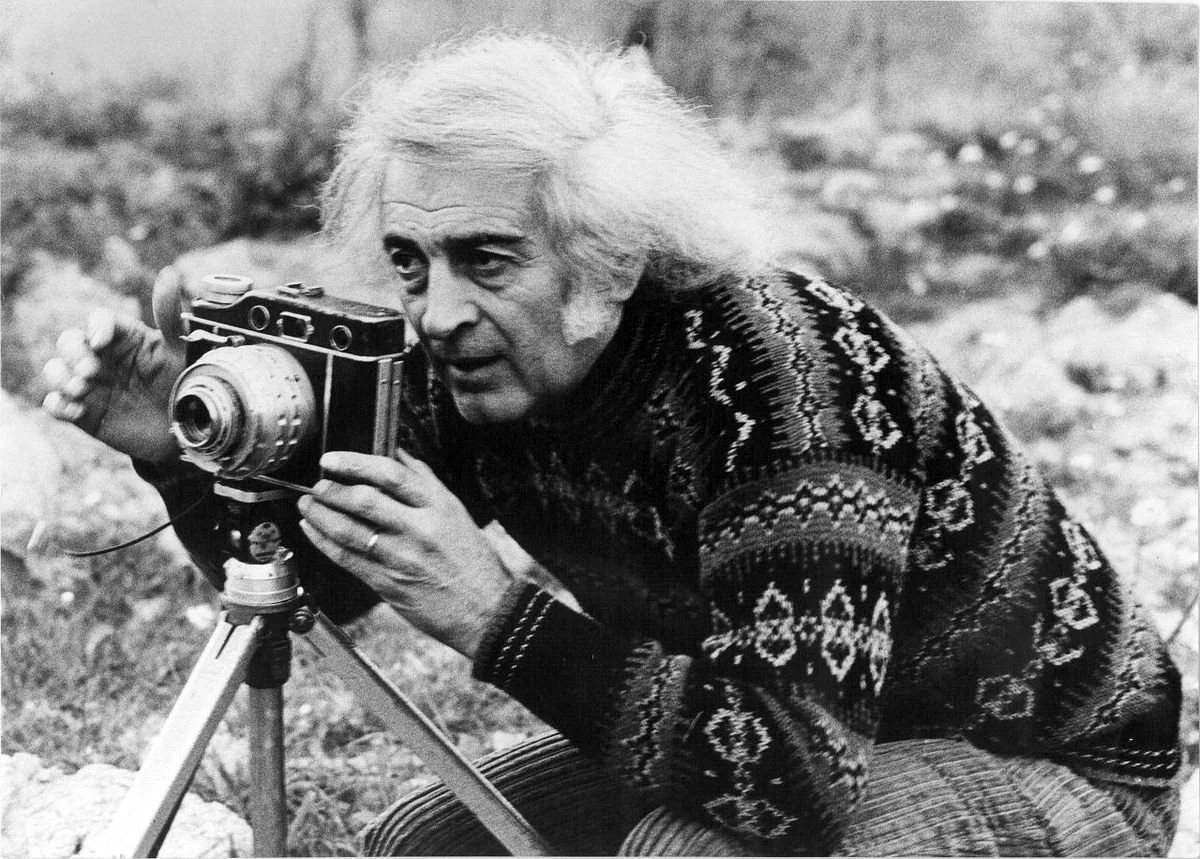

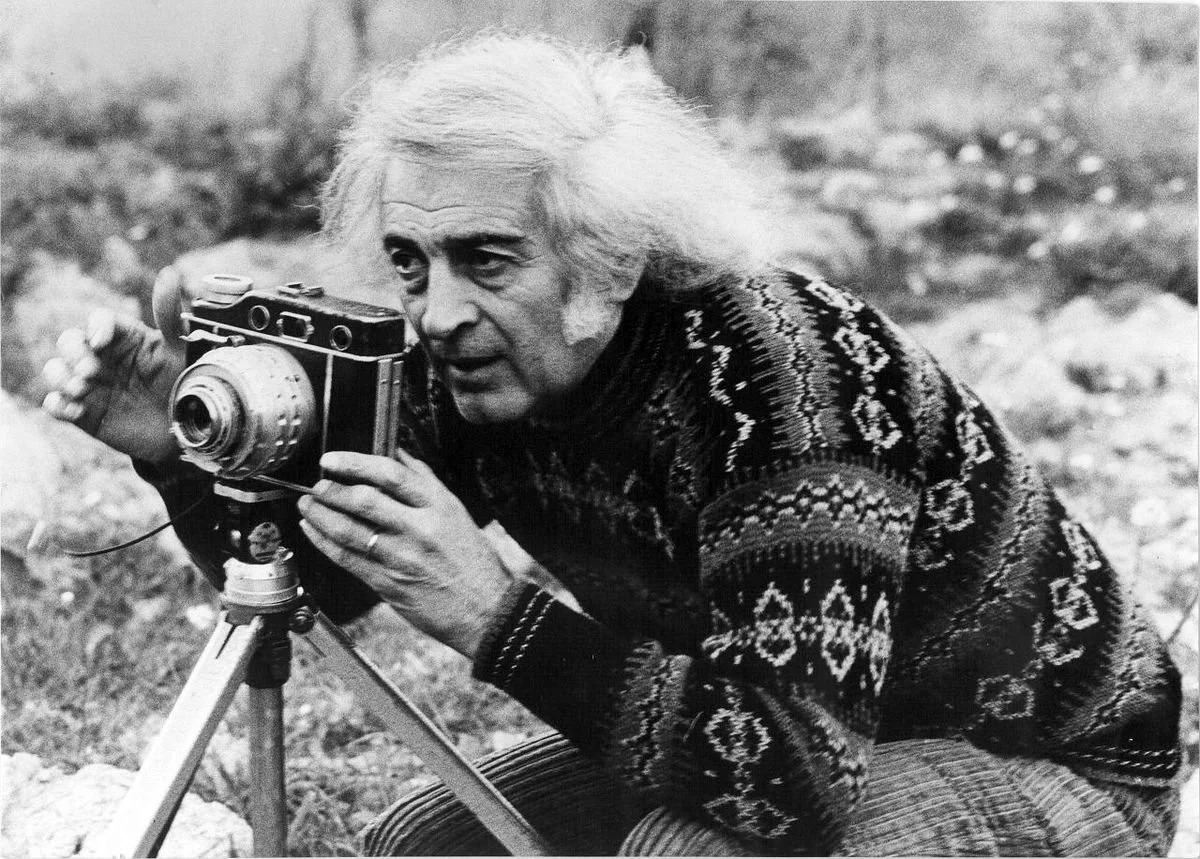

MARIO GIACOMELLI

Mario Giacomelli is one of the most important italian artists of all the times using photography as a medium.

Giacomelli developed his photographic technique in order to actualise his notion of his camera as one of his own limbs (as he terms it: ‘an extension of my idea’). Giacomelli’s creative approach maps out “escape routes away from convention.” He pushed his camera to its extremes, modifying it to fit his precise needs, and abusing it. His camera became a means of deconstructing reality, or rather deconstructing the common conception of reality as static.

Giacomelli’s oeuvre is a system of continual mutations; it is a whole consisting of interrelated parts; a living organism. Each series is not a closed chapter. Giacomelli continually redefined his photographic series by returning to certain images like snippets from past conversations. He revitalised them by setting them in new contexts, seeking to ‘breathe life into things via the pretext of Photography.’

In his later work, Giacomelli took on the role of performer. This performative element was fundamental throughout the course of his practice, the structure of which is highly ritualistic, with repeated gestures assuming symbolic value. Giacomelli’s photographic image is, therefore, far from an instantaneous snap, disconnected from time’s contingency. It assumes and exudes a certain solemnity. The significance with which Giacomelli charges each image enters it into an absolute, atemporal, and thus eternal, realm, in which he sought to immerse himself. Photography is the “pretext” that allows Giacomelli to enter the world. It is as if his whole life led up to the autobiographical focus of his final work, with its fusion of action and speech, life and art.

Giacomelli pro-duces the image, in the etymological sense of the word: he extracts it from the depths of his being in order to render it visible to himself. It is for this reason that Giacomelli considered himself a spectator, part of a precise and ritualistic methodology. It is this dual role of creator-spectator that makes Giacomelli feel so contemporary: he abandoned objectivity in favour of absolute subjectivity, and found himself face to face with his own creativity, as if he were standing before a mirror.

For Giacomelli, photography was not a simple declaration of “this happened in a specific place at a specific time,” as is the case for documentary photography. Instead, his photography absorbs interrelated clusters of subjects and meanings. These clusters are in continual movement (Giacomelli transferred subjects from one print series to another, took photographs of photographs, inserted old photographs into new series, and used superimposition, resulting in images in which present subjects enter scenes from the past). His photographs are in a continual state of change (in his darkroom, Giacomelli altered the textures of reality). The subjects are historically and chronologically unanchored (isolated from their context by Giacomelli’s bitten whites and rendered two-dimensional by his use of daytime flash, a zoom lens, and tight cropping). Giacomelli’s network of images is a continuum of signs and symbols. For Giacomelli, photography was not a tool for testimony. The subjects of his photographs are pure, free-moving signifiers which derive their meaning from being multiplied, repeated, remodelled, and set into new dialogues. This approach aligns Giacomelli’s work with the idea of the Informal in art, and also enables us to trace a method which spans his practice.

Giacomelli’s creative method allowed him to reset his relationship with this realm of possibility time and again. This is achieved through his systemisation of his whole photographic oeuvre. When Giacomelli finally decided to enter the frame of the photograph, as he did in his later work, using a self-timer, the space is desolate, lifeless, devoid of human subjects, and only inhabited by fake animals and crumbling houses (distilling the notion of subject/signifier to its most essential form). Giacomelli wanted to enact a revitalisation of the inanimate, using fake animals and masks to highlight photography’s ability to animate something that would have otherwise remained inanimate. What does this mean? This means that Giacomelli immerses himself in a “magical” scene (he often defined photography in these terms), which is capable of (symbolically) elapsing every distance, even that between life and death. The inanimate thing gains new life when it assumes its place in the new order of reality mapped out by photography. It is here, in this void of possibility, this realm of infinite potential, that Giacomelli gets closest to the crux of his conception of photography (he defines photography as ‘getting under the skin of reality’): in his final series, he physically enters the space of the photograph, via self-portraiture.

(Katiuscia Biondi in Mario Giacomelli. Sotto la pelle del reale, Ed. 24 Ore Cultura, 2011)

Books by Mario Giacomelli

QUESTO RICORDO LO VORREI RACCONTARE